(If you haven’t yet read the first part of Resilience Rediscovered, please click the link and read it first, it’s worth it.)

In July 1944, Anne Frank wrote:-

“In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.”

Less than three weeks later, she and her family were betrayed to the Gestapo, arrested, and ultimately killed in the horrors that followed.

From Eindhoven to Kraków

Before we left England, I’d spoken to my half-brothers about visiting Auschwitz. I had recently read The Choice by Edith Eger, a profound exploration of survival and resilience, and it had inspired me to confront this dark chapter of history.

Both of my brothers agreed it would be a meaningful stop on our journey.

Originally, we planned to continue our trip from Arnhem by riding through Germany, visiting the sites linked to the three P.O.W. camps where Cyril had been held. These camps were places where our shared family history intersected with global tragedy - an important part of Cyril’s journey as a soldier and prisoner.

After some extensive research, it didn’t take long before we realised the camps no longer existed - they had been replaced many decades before by modern housing estates. The mental image of three burly Englishmen pulling up outside someone’s home on noisy bikes seemed wildly inappropriate.

And besides, the thought of adding another 1,500 road miles to our trip - when we were already contending with aching bodies and sore arses - didn’t seem appealing.

Prudence won out, and we decided to fly instead.

Heading East

We drove to Eindhoven, found a secure place to leave our bikes, crashed in the hotel and early the next day, made our way to the airport. As we walked out to our aircraft, we spotted a number of C130’s lifting off, likely en route to Ginkelse Heide - the very site of the parachute drops during Operation Market Garden, 75 years earlier. It was a poignant moment, and it felt like the weight of history was about to follow us eastward.

Just under two hours later, we landed in Kraków.

A Different Kind of Exploration

Upon arrival in the Kraków, we decided to start our trip with an activity that, admittedly, might not be to everyone’s taste. There are many ways to experience history, we wanted to begin our visit by connecting with the past in our own way. So, we headed to a local shooting range to fire some World War II-era weapons.

Almost every weapon our ancestor might have used during his wartime service was available, except for the Bren machine gun.

However, they did have the infamous German MG 42 and I just couldn’t resist the opportunity to fire it. I hadn’t really thought it through at the time - it was an indoor range.

The moment I pulled the trigger, the air displacement hit all of us like a shockwave. The sound and vibrations weren’t just loud; they reverberated through my entire body. The sheer force of it was unlike anything I had experienced before, and it was only a fraction of the reality soldiers like Cyril faced.

He had once described the MG 42 as a "buzzsaw," and seated there, blasting away, I finally understood what he meant.

It was terrifying to imagine that wall of hot metal coming at you in the chaos of battle, knowing how brutally efficient it was at cutting down soldiers and forcing them to keep their heads lowered, or pay the price.

As we walked away from the range, the experience left us all with a deeper respect for those who had to face such relentless weaponry in the heat of war. It was a sobering reminder of the unimaginable psychological and physical toll that men like our grandfather endured - and how their resilience in the face of such terror speaks to the strength of the human spirit.

Exploring Kraków: History’s Shadows

The next day, we embarked on a guided walking tour of Kraków, a city where layers of history unfold at every turn. This experience immersed us in Poland’s complex past, from the resilience of the Polish resistance to the unspeakable atrocities committed by both the Nazis and the Soviets. It was a scorching day, and the heat seemed to intensify the emotional weight of each step we took, as though the ground itself carried the pain of so many lost lives.

One of the most poignant moments of the tour took us to Jozefa 12, where a scene from Schindler’s List had been filmed. The spot where Jewish families were violently forced from their homes for the film mirrored the real-life events it was based on.

Standing there, imagining what it would have been like to witness such cruelty firsthand, was deeply moving. You could almost feel the echoes of the past still clinging to the air.

As the day began to wind down, we found ourselves in Plac Bohaterów Getta (Ghetto Heroes Square), and the shift in mood was palpable. Here, rows of oversized metal chairs form a haunting memorial, each one representing the Jewish lives uprooted from the Kraków Ghetto. Between 1942 and 1943, over 15,000 Jews were forcibly deported from this square to concentration camps like Auschwitz and Płaszów.

The memorial’s design, symbolising the emptiness left behind by those who never returned, serves as a chilling reminder of the horrors that took place here. As the sun began to set, the shadows grew longer, and the square seemed even more silent, as if the very air bore witness to the atrocities committed.

It was a space of immense quiet. The weight of history pressed down upon us, and we stood there, reflecting on the enormity of what had occurred.

A Quiet Pause

After a day so heavily steeped in the gravity of the past, we sought a quiet space to collect our thoughts. The sun was setting, casting long shadows across the streets, as if the terror of those days followed us still.

We wandered through the quieter parts of the old city, our minds full, yet our hearts heavy. It felt strange to be moving freely through streets that had once been a prison for so many, yet here we were, trying to make sense of the unimaginable.

At some point, we simply stopped walking, found a bar and sat in silence. There were no words, just the weight of everything we had seen, everything we had learned.

It was impossible not to reflect on the fragility of life and the passage of time. It felt like the past was speaking to us, not just from the memorials or the stories, but as if the stones themselves were crying out, asking us to remember - to never forget.

An Evening in Kazimierz

As night fell, we found ourselves in Kazimierz, the old Jewish Quarter. The juxtaposition of history’s darkest shadows with our present-day comforts felt surreal.

We sat in a small restaurant near the Old Synagogue, sipping drinks as a trio of musicians arrived and began playing a haunting folk melody that seemed to hang in the air, echoing the emotions of the day.

In that moment, the contrast was overwhelming.

Just a few blocks away, we had stood in places where the unimaginable had unfolded - where families had been torn apart, where entire communities were erased.

Sitting under the same sky, we were acutely aware of how much history had shifted, how fortunate we were to live in a world so distant from the one that had existed so close by.

But as we enjoyed the peace of the evening, we knew the hardest part of our journey was yet to come...

Auschwitz: An Overwhelming Reality

The next morning, we crammed ourselves into the hire car - an unassuming Toyota Prius - and, as almost everyone does with a rental, made a game of ‘thrashing the bollocks’ out of it before something went wrong.

It was a fleeting moment of humour, the last bit of lightness we could muster before the day’s heavy reality set in.

The drive started on a motorway, but soon enough, we found ourselves winding through the serene Polish countryside. Fields rolled by under a peaceful sky, a stark contrast to what awaited us.

After about 90 minutes, we drifted into Oświęcim - innocuous at first glance, but known to the world ever since as Auschwitz…. and then, we arrived at the camp.

The first shock was the sheer volume of people.

I’d expected a quiet, reflective space, but instead, the entrance was bustling with visitors - almost like queuing for an attraction. This contrast was unsettling, but the true horror lay beyond the gates - the sheer scale of cruelty and butchery was almost beyond reason.

Walking through the barracks of Auschwitz I was an experience that defied comprehension. The piles of shoes, many of them small enough to have belonged to children, and the stacks of eyeglasses and other personal items were haunting.

It wasn’t just the scale - though the sheer quantity of belongings left behind was staggering - it was the intimate, human details that hit hardest.

These everyday objects represented individuals, each with a story, a family, and a life stolen from them. It was impossible to grasp the magnitude of suffering that had taken place within these walls.

Outside, we eventually stood before the small gas chamber, a chilling precursor to the industrialised death machinery of Birkenau.

Stepping inside was suffocating. The room, though not large, felt claustrophobic, the air heavy. The walls, still marked by the desperate scratch marks of fingernails, were a silent testimony to the unimaginable terror of those final moments.

The sheer brutality of what had occurred here was far beyond anything most of us will ever encounter in our everyday lives, a cruelty so monstrous it was difficult to fully comprehend.

As sobering as the morning had been, I couldn’t have imagined that what awaited us at Auschwitz II-Birkenau would be even worse.

I was wrong…

Already questioning my own limits, I realised as we approached Birkenau, or Auschwitz II, that what lay ahead would push my understanding of resilience even further.

What I thought I knew about human suffering was about to be irrevocably changed.

Birkenau: A Place of Unimaginable Horror

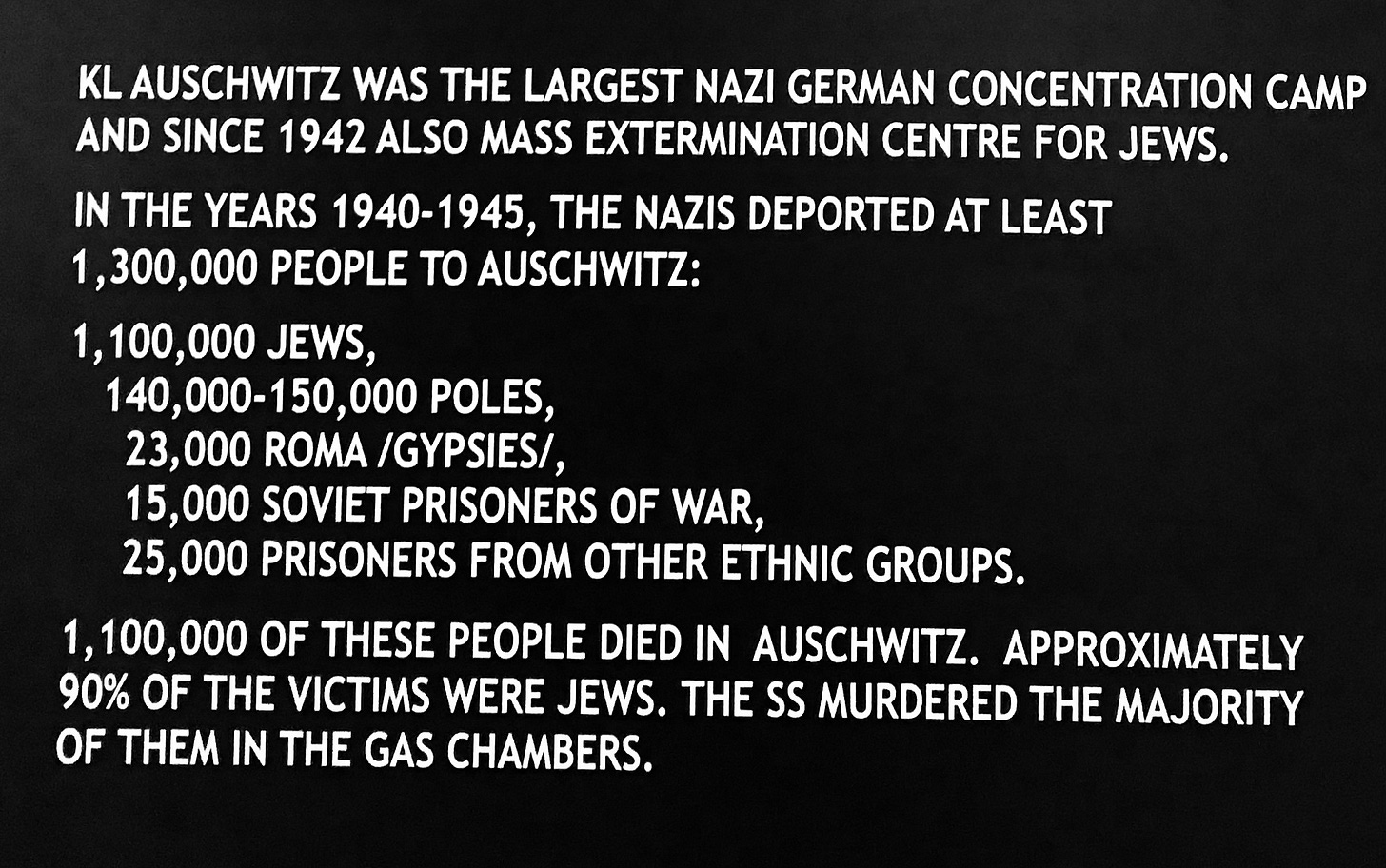

In the afternoon, we made our way to Birkenau, or Auschwitz II, the larger and more industrialised of the two camps. While Auschwitz I felt oppressive and claustrophobic, Birkenau was sprawling - some 1.5 million square metres - its vastness unfathomable, stretching out into the distance like a bleak, endless horizon.

At the heart of the camp, between the two main gas chambers, stands Memorial Park, a grim reminder of the scale of destruction that took place here.

Between 1943 and 1944, an average of 5,000 people were murdered, gassed and incinerated each and every day - a figure difficult to fathom. The Nazi regime’s relentless pursuit of extermination turned these death chambers into factories of human destruction.

A Moment of Solitude

After spending time reflecting at the Memorial Park, I felt an increasing urge to be alone, away from the shared weight of grief and even the familiar presence of my brothers.

We had all felt it - the crushing burden of this place, challenging our own ideas of resilience. But something inside me needed isolation, a space to process the thoughts gnawing at my mind:

Would I have survived this?

Would I have found the strength to endure the horrors faced by these men, women, and children? Or would I have crumbled under the cruelty?

These questions haunted me as I wandered nearly a kilometre away - towards the washrooms near the railhead entrance, seeking solitude where the magnitude of this place could fully wash over me.

The sound of voices caught my attention, and I felt a vague irritation at the interruption. It was a large group of teenagers - some holding small Israeli flags - most likely part of a March of the Living trip.

They weren’t disruptive, but in that moment, I craved silence. I had come here to confront my own thoughts, to wrestle with the horrors these grounds had witnessed. And their presence, though respectful, reminded me that we were all grappling with the past in different ways. But selfishly, I wanted stillness - a moment to feel alone in the enormity of it all.

Then I noticed them…

Three security personnel, subtly repositioning themselves between me and the students.

For a brief second, our eyes met, and there was an unspoken acknowledgment. A small, almost imperceptible nod, as if to say, "We see you."

And I stopped.

Waiting as they guided their charges further along, I stood still, silently until they had moved on before I continued towards the building.

And in that pause, a strange tension rose in me - a pull between past and present.

For a fleeting moment, the weight of judgment settled heavily upon me. I was just a stocky, bald man in a black leather jacket, standing in a place where so many had been killed for merely how they looked. Now, here I was, seen as a potential threat - not from malice, but from appearances alone.

The sting of it was sharp.

Suddenly, I was pulled from my reflection, back to the present, only to be hurled into the past once again - back to the propaganda, the caricatures that had dehumanised entire groups of people for expedience. And here I stood, feeling - if only for a heartbeat - what it was like to be judged by appearance.

It was a surreal moment, an unsettling intersection of time. I thought of the political rhetoric still so prevalent today, leaders who vilify entire groups, just as it had been done here decades ago.

A sobering reminder of how fragile history truly is, and how quickly the flames of hatred can rise again.

A Sobering End

We left Birkenau deeply reflective, the weight of the day hanging heavy over us. Eight hours had passed, yet the imprint of what we had seen and learned would last a lifetime. The drive back to Kraków was slow and silent, as if words would have been inadequate to express the depth of what we were feeling.

That night, we sought to lighten the mood. We went out and got blind drunk - an unconscious way of escaping, if only for a brief moment, from the harrowing reality we had just confronted.

Early the next day, we boarded our flight back to Eindhoven, where we discovered one of my brothers had lost his motorbike key somewhere along the trip!

It was a comical, almost absurd contrast to the seriousness of what we had experienced, and it was here that we parted ways.

One of us made his way back to England alone, while I stayed in Eindhoven with the other, waiting for a spare key to be shipped from the UK.

That night, sitting in a bar surrounded by a noisy football crowd, my phone rang.

It was my daughter, in tears, telling me something had happened. Had I been sober, I would have hopped on my bike there and then and driven the eight hours home. Instead, we cut our evening short, and the next morning, began the long drive back to the Channel Port.

Somewhere along the M20, my remaining brother and I parted ways for the last time on this journey. He headed north, and I peeled off south, the road ahead of me feeling both familiar and strangely distant.

Final Reflections: A Shift in Perspective

Resilience isn't just a quality we find within ourselves; it’s a link to those who came before us, a thread connecting us to the trials they faced and survived. As I left this journey behind, it felt as if each place we’d visited left a mark, a reminder of the strength embedded in human spirit - even in the face of unfathomable cruelty. And in my quiet moments, I’ll carry this journey forward as a testament: a way of remembering not only the horrors, but also the courage it takes to hold onto hope in dark times.

This journey served as a stark reminder that sometimes, in life, we become so absorbed in our own struggles, in our own pain, that we forget how easy we truly have it...

"Resilience Rediscovered" was never meant to diminish personal struggles, but rather to offer perspective. There is value in looking beyond our immediate troubles, in lifting our gaze from our own pain and seeing what others have endured. Because for me, whenever someone says, "Things could always be better," I silently respond, "Yes, but they could also be so much worse."

It is from that place that I find my strength.

As I reflected on my journey, I realised these experiences had taught me powerful lessons in resilience, which I now want to share with you:

Broaden Your Perspective: When life feels overwhelming, it’s easy to get lost in the details of your own struggles. Taking a step back and reflecting on the larger picture - whether that’s through stories of history, the challenges others face, or even world events - can help shift your perspective and remind you of the resilience that lies within you.

Seek Connection: Resilience doesn’t have to be a solitary journey. One of the most profound lessons from Auschwitz was how people survived by leaning on one another. Sharing your burdens with others, even just by talking, can provide a much-needed reminder that you’re not alone.

Embrace Small Acts of Strength: Resilience isn’t always about monumental efforts. Sometimes, it’s found in the smallest of actions - getting up and moving forward when you don’t feel like you can, making a choice to look for hope amid the pain, or simply staying present in the moment when everything feels overwhelming.

Connect With Me

Subscribe to Life’s Lessons Unpacked for insights into building resilience, reconnecting with your history, and thriving through life's most difficult moments.”

If this story resonated with you, or if you have your own reflections on family history, resilience, or life’s unexpected journeys, I’d love to hear from you. Drop a comment or as ever, leave a ❤️ or reach out directly - I’m always open to connecting with readers interested in growth, history, and understanding the complexity of life.

By subscribing, you’ll receive:

Practical strategies for developing emotional resilience and reconnecting with yourself.

Real-life stories and reflections on navigating relationships, parenthood, and personal growth.

Insights drawn from 20 years of coaching experience, designed to help you thrive during life’s most challenging times.

An incredibly powerful and touching memoir, especially your words about Berkenau. I've still not been brave enough to go.

I visited Auschwitz in March 2007 on a school history trip that also took us to Berlin and Krakow. It’s impossible to describe the eerie and chilling quiet of that place. The collections of baby clothing in particular stay etched in my brain and, having two younger brothers, it was hard to avoid picturing their own clothing there in the display cabinets. Eyeglasses more than you could ever estimate the number of, the carpets made from human hair and the smallness and haunting finality of the gas chambers themselves. I slept poorly that night, not appreciating then quite how transformational this experience had been, the realisation of the smallness of self, the ingenuity of evil and the fleetingness of life.